What Is Rail Transloading? Complete Guide & Case Study

Getting goods from origin to destination is rarely a straight line. When highways clog with traffic or drivers are scarce, switching from trucks to trains can drastically reduce costs. Rail transloading – the practice of moving freight between trucks and railcars – makes this possible. A single railcar can replace three to four truckloads, and trains are three to four times more fuel‑efficient. With the U.S. rail network spanning nearly 140,000 miles and intermodal volumes surging 6.4 % year‑over‑year in early 2025, understanding rail transloading is essential for modern supply chains. This guide explains how it works, why it matters and when to use it.

What Is Rail Transloading?

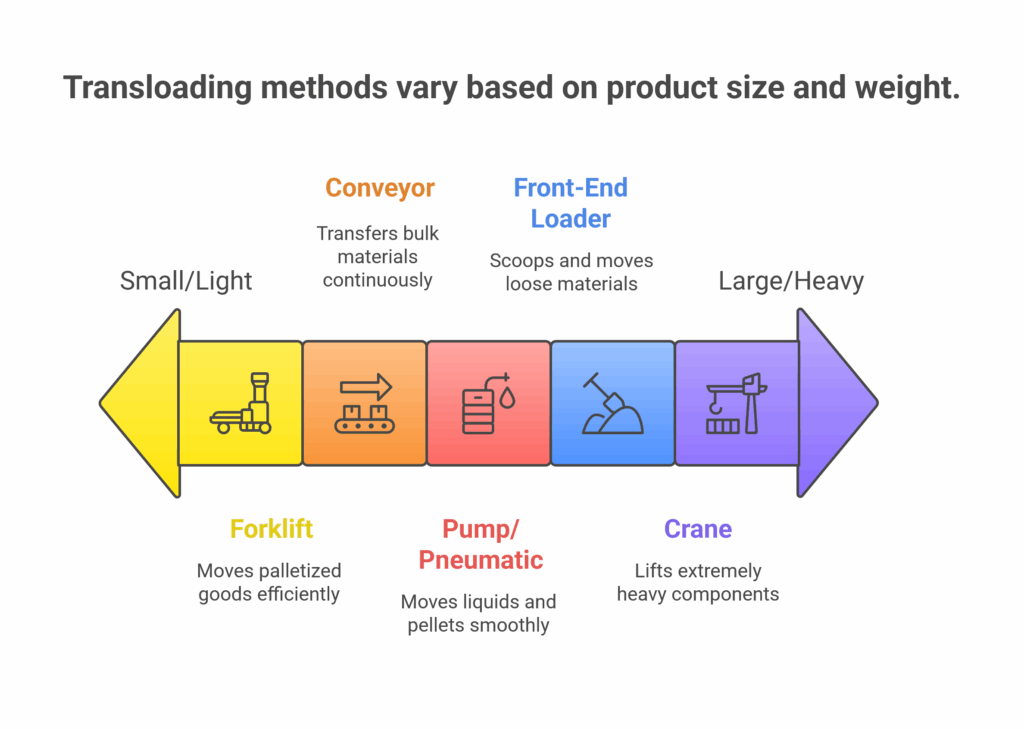

Rail transloading is a transfer process that links trucks and railcars so shippers can take advantage of rail for long hauls without being located on a rail spur. Goods are loaded onto trucks, transported to a transload facility and then transferred to railcars using equipment such as forklifts, conveyors, pumps or cranes. The railcars carry the freight across the country. At the destination, the cargo may be transferred back to trucks for final delivery. Unlike intermodal shipping, which uses standardized containers and leaves the cargo untouched, transloading often involves moving bulk or break‑bulk goods between different types of equipment.

How Rail Transloading Works

Origin, Destination & Door‑to‑Door Scenarios

- Origin transload (no tracks at origin): Trucks pick up products from the shipper’s facility, deliver them to a transload yard, where they are loaded onto railcars. The railcars then carry the goods to the rail‑served receiver.

- Destination transload (no tracks at destination): Goods originate at a rail‑served facility, travel by rail and are unloaded to trucks at the destination transload yard for final delivery.

- Door‑to‑door transload (no tracks at either end): Trucks handle first and last mile; rail handles the main leg. The freight is transloaded to and from railcars at both origin and destination.

Equipment and Facility Requirements

Transload facilities employ specialized equipment tailored to product types. Forklifts move palletized goods; conveyors handle bulk commodities such as grains or aggregates; pumps and pneumatic systems transfer liquids like ethanol or biodiesel; cranes lift heavy or oversized loads such as steel beams or wind turbine blades. Facilities also need bonded and grounded tracks, spill‑containment systems, certified scales and sometimes steam boilers for heating or cleaning tanks. The design must include sufficient track length and storage space to accommodate multiple railcars and trucks.

Benefits of Rail Transloading vs. Trucking/Intermodal

Cost & Efficiency

Long‑haul trucking is expensive when fuel, labor and highway congestion are considered. A 2024 Costmine study reported that rail transport costs about $0.160 per ton‑mile for a 1,000‑mile trip, while trucking can exceed $3 per ton‑mile. Because one railcar carries three to four truckloads and trains are three–four times more fuel‑efficient, transloading delivers significant cost savings. Shifting 10 % of long‑distance freight from trucks to trains would save nearly one billion gallons of fuel annually.

Environmental & Social Impact

Railroads move one ton of freight 470 miles per gallon of fuel. Replacing long‑haul trucking with rail reduces greenhouse‑gas emissions and eases highway congestion. Research sponsored by the U.S. Department of Transportation found that six locomotives can substitute for about 1,000 tractor‑trailers, halving carbon monoxide emissions. For businesses striving to meet sustainability targets, transloading helps shrink carbon footprints.

Flexibility & Market Reach

Transloading gives shippers without rail access the ability to use rail networks. Railroads serve major economic corridors, ports and border crossings; the U.S. network comprises nearly 140,000 route miles and is operated by seven Class I and hundreds of regional/short‑line railroads. By transloading, companies can reach new markets, import/export through coastal ports and diversify carriers—breaking monopolies that increase rates. Transloading covers a wide spectrum of products including lumber, steel, aggregates, grains, liquids, perishables and consumer goods.

Inventory & Supply‑Chain Resilience

Transloading adds buffer storage. Shippers can stage inventory at transload yards near customers, shortening delivery times and reducing demurrage fees. Freedonia Focus Reports forecast that U.S. rail freight revenues will grow 4.7 % per year through 2025, a reflection of supply‑chain managers seeking resilience and cost efficiency. Meanwhile, the AAR reported that intermodal volumes climbed 6.4 % year‑over‑year in early 2025, showing that businesses increasingly rely on multimodal solutions.

When to Use Rail Transloading

Use the following decision matrix to determine whether rail transloading is right for your shipment:

| Scenario | Suitability of rail transloading | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Long‑distance, heavy or bulk shipments | High | Rail offers lower per‑unit costs and can move bulk commodities (grains, aggregates, coal) more efficiently than trucks. |

| Limited truck capacity or driver shortages | High | Railcars replace multiple trucks and mitigate driver scarcity, freeing up trucking capacity for local deliveries. |

| No rail spur at origin/destination | High | Transloading bridges the gap via trucks, enabling rail use without capital investment. |

| Time‑sensitive, containerized goods | Moderate | Intermodal shipping may be better for containerized cargo that does not require handling; transloading is useful if the facility can stage goods near customers for quick distribution. |

| Hazardous materials or regulated commodities | Requires caution | Transloading is permitted but subject to HMR and EPCRA regulations. Facilities must have spill containment, grounding and trained operators. |

| Short hauls (under ~300 mi) with accessible roads | Low | Trucking alone may be more cost‑effective for short distances because rail’s loading/unloading costs may outweigh fuel savings. |

Transloading differs from intermodal shipping: intermodal involves containerized cargo that remains inside the same container across modes, while transloading involves transferring bulk or non‑containerized cargo between different vehicles. Choose transloading when you need to move large, heavy or irregularly shaped goods that do not fit into standard containers, or when your facility lacks a rail spur.

Regulations, Safety & Compliance

Handling hazardous or bulk commodities requires compliance with federal regulations. The Department of Transportation’s Hazardous Materials Regulations (HMR) specify that transferring hazardous materials from one packaging to another (bulk‑to‑bulk, bulk‑to‑non‑bulk or vice versa) for continued movement is a transportation function, regardless of whether it occurs at an intermodal facility. Storage incidental to movement is also considered transportation and remains subject to HMR. Facilities must have emergency response plans, spill containment systems, grounding and bonding equipment and certified operators.

The Environmental Protection Agency clarifies that hazardous chemicals stored at rail yards fall under the Emergency Planning and Community Right‑to‑Know Act (EPCRA) if they are not under active shipping papers. Employers must provide Material Safety Data Sheets (MSDS), and workers are protected by OSHA standards. Selecting a transloading partner with robust safety programs, employee training and regulatory compliance is critical.

Selecting a Transloading Partner & Facility

When evaluating transloading providers, consider the following criteria:

- Location & access: Choose facilities near major highways, Class I railroads or ports to minimize drayage costs. Short‑line connections can provide market reach while reducing congestion.

- Equipment & capacity: Ensure the facility has the right equipment-forklifts, cranes, conveyors, pumps-and adequate track space and storage to handle your cargo type.

- Safety & compliance: Verify that the provider adheres to HMR and EPCRA regulations, has spill‑containment systems, grounding tracks and certified scales.

- Technology & visibility: Modern transloading facilities use yard‑management systems, real‑time tracking and sensor technology to optimize operations and reduce demurrage.

- Service expertise: Look for operators experienced with your commodity-bulk grains, hazardous liquids, oversize equipment-and who can coordinate first/last‑mile trucking and cross‑border customs.

- Contracts & pricing: Evaluate pricing structures (per ton, per carload, demurrage terms) and ensure transparency. Ask about minimum volumes and service guarantees.

Future Trends & Technology in Transloading

The transloading industry is evolving rapidly. Freedonia predicts that U.S. rail freight revenues will grow 4.7 % annually through 2025, driven by persistent truck driver shortages, rising fuel costs and environmental regulations. At the same time, intermodal volumes are climbing, as noted by the AAR’s 2025 report. To support growth, transloaders are adopting automation and real‑time tracking, using yard‑management software that monitors car locations, demurrage clocks and inventory . Sensors for temperature and humidity ensure product integrity, especially for perishables and hazardous materials. Renewable diesel and electrified yard equipment are reducing the environmental footprint.

Conclusion

Rail transloading combines the long‑haul efficiency of trains with the flexibility of trucks, allowing shippers to move goods cost‑effectively and sustainably. With one railcar replacing multiple truckloads and trains delivering fuel efficiency four times better than trucks, transloading offers significant cost and environmental benefits. The rise of intermodal volumes and forecasts of rail freight growth show that transloading is a critical component of resilient supply chains. By understanding the process, regulations and selection criteria, businesses can leverage transloading to reach new markets, manage inventory and meet sustainability goals.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ) – OLIMP Warehousing

Q: What is rail transloading and how does it work?

Transloading transfers goods between trucks and railcars so that shippers can use efficient rail transport without a rail spur. Trucks deliver cargo to a transload facility, where operators use forklifts, conveyors, pumps or cranes to load railcars; at the destination the process reverses.

Q: When should I choose rail transloading instead of trucking?

Transloading is ideal for long‑distance, heavy or bulk shipments where rail’s lower cost per ton‑mile offsets handling expenses. It also suits locations without rail access and helps mitigate driver shortages. For short hauls, pure trucking may be cheaper.

Q: What products can be transloaded?

A wide range of commodities—including lumber, steel, paper, sand, plastic pellets, grains, ethanol, biodiesel, transformers, wind turbine blades and perishables—can be transloaded using appropriate equipment.

Q: Is rail transloading the same as intermodal shipping?

No. Intermodal shipping uses standardized containers and keeps the cargo inside the same container across modes, whereas transloading involves transferring cargo from one vehicle to another and is often used for bulk or irregularly shaped goods.

Q: What regulations apply to transloading hazardous materials?

The U.S. DOT’s Hazardous Materials Regulations (HMR) classify transloading as a transportation function and require compliance when transferring hazardous materials. Facilities must also adhere to EPA reporting if hazardous chemicals are stored beyond active shipping papers and to OSHA safety standards.

Q: How do I find a transloading facility near me?

Many railroads and logistics providers maintain directories of transload facilities. Consider contacting local short‑line railroads, Class I carriers or third‑party logistics providers. Evaluate facilities based on equipment, location, safety and service expertise.

You may be interested in

What Is Transloading? Definition, Services & Facilities Guide

Transloading moves cargo between trucks, trains and ships to cut costs and speed delivery. It means unloading freight from one mode (like a ship’s container) and reloading it onto another (such as a freight train or trailer). This process lets importers and shippers mix modes – using rail or ocean for long hauls and trucks […]

Intermodal Drayage: Definition, Benefits, and Key Differences

For shippers and logistics managers, intermodal drayage is the short-haul trucking segment of a longer freight route. It involves moving containers by truck between ports, rail terminals, and warehouses-typically within a 15–50 mile radius. This first-mile/last-mile trucking leg bridges larger shipping modes (ships, trains, and trucks), keeping cargo flowing smoothly and reducing port congestion. Intermodal […]

Intermodal Shipping: The Smart, Efficient Way to Move Freight

Intermodal shipping refers to moving freight by two or more transportation modes (truck, rail, ship, etc.) using standardized containers. Cargo stays sealed inside its container during transfers, reducing handling and speeding up delivery. This containerized approach cuts costs and transit time for long-distance shipments, making intermodal freight shipping a cost-efficient, secure method to move goods. […]

Ready to streamline your warehousing needs?

Request a quote today and discover how OLIMP's tailored solutions can optimize your operations